The Berlin Interpretation defined eight high-value factors:

[18]

- The game uses random dungeon generation to increase replayability.[19] Games may include pre-determined levels such as a town level common to the Moria family where the player can buy and sell equipment, but these are considered to reduce the randomness set by the Berlin Interpretation.[18] This "random generation" is nearly always based on some procedural generation approach rather than true randomness. Procedural generation uses a set of rules defined by the game developers to seed the generation of the dungeon generally to assure that each level of the dungeon can be completed by the player without special equipment, and also can generate more aesthetically-pleasing levels.[20]

- The game uses permadeath. Once a character dies, the player must begin a new game, known as a "run", which will regenerate the game's levels anew due to procedural generation. A "save game" feature will only provide suspension of gameplay and not a limitlessly recoverable state; the stored session is deleted upon resumption or character death. Players can circumvent this by backing up stored game data ("save scumming"), an act that is usually considered cheating; the developers of Rogue introduced the permadeath feature after introducing a save function, finding that players were repeatedly loading saved games to achieve the best results.[8] According to Rogue's Michael Toy, they saw their approach to permadeath not as a means to make the game painful or difficult but to put weight on every decision the player made as to create a more immersive experience.[21]

- The game is turn-based, giving the player as much time as needed to make a decision. Gameplay is usually step-based, where player actions are performed serially and take a variable measure of in-game time to complete. Game processes (e.g., monster movement and interaction, progressive effects such as poisoning or starvation) advance based on the passage of time dictated by these actions.[18]

- The game is non-modal, in that every action should be available to the player regardless where they are in the game. The Interpretation notes that shops like in Angband do break this non-modality.

- The game has a degree of complexity due to the number of different game systems in place that allow the player to complete certain goals in multiple ways, creating emergent gameplay.[18][22] For example, to get through a locked door, the player may attempt to pick the lock, kick it down, burn down the door, or even tunnel around it, depending on their current situation and inventory. A common phrase associated with NetHack is "The Dev Team Thinks of Everything" in that the developers seem to have anticipated every possible combination of actions that a player may attempt to try in their gameplay strategy, such as using gloves to protect one's character while wielding the corpse of a cockatrice as a weapon to petrify enemies by its touch.[23]

- The player must use resource management to survive.[18] Items that help sustain the player, such as food and healing items, are in limited supply, and the player must figure out how to use these most advantageously in order to survive in the dungeon. USGamer further considers "stamina decay" as another feature related to resource management. The player's character constantly needs to find food to survive or will die from hunger, which prevents the player from exploiting health regeneration by simply either passing turns for a long period of time or fighting very weak monsters at low level dungeons.[24] Rich Carlson, one of the creators of an early roguelike-like Strange Adventures in Infinite Space, called this aspect a sort of "clock", imposing some type of deadline or limitation on how much the player can explore and creating tension in the game.[25]

- The game is focused on hack and slash-based gameplay, where the goal is to kill many monsters, and where other peaceful options do not exist.[18]

- The game requires the player to explore the map and discover the purpose of unidentified items in a manner that resets every playthrough. The identity of magical items, including magically enchanted items, varies from run to run. Newly discovered objects only offer a vague physical description that is randomized between games, with purposes and capabilities left unstated. For example, a "bubbly" potion might heal wounds one game, then poison the player character in the next. Items are often subject to alteration, acquiring specific traits, such as a curse, or direct player modification.[18]

Low-value factors from the Berlin Interpretation are:

[18]

- The game is based on controlling only a single character throughout one playthrough.

- Monsters have behavior that is similar to the player-character, such as the ability to pick up items and use them, or cast spells.

- The game aimed to provide a tactical challenge that may require players to play through several times to learn the appropriate tactics for survival.[18]

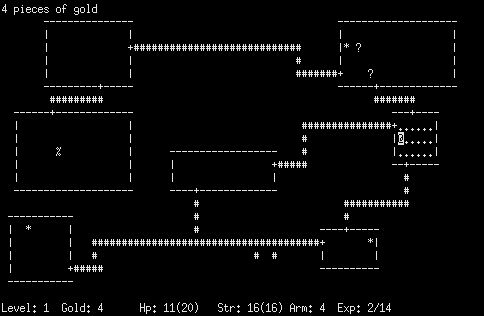

- The game is presented using ASCII characters in a tile-based map.

- The game involves exploring dungeons which are made up of rooms and interconnecting corridors. Some games may have open areas or natural features, such as rivers, though these are considered against the Berlin Interpretation.[18]

- The game presents the status of the player and the game through numbers on the game's screen/interface.

Though this is not addressed by the Berlin Interpretation, roguelikes are generally single-player games. On

multi-user systems,

leaderboards are often shared between players. Some roguelikes allow traces of former player characters to appear in later game sessions in the form of

ghosts or

grave markings. Some games such as NetHack even have the player's former characters reappear as enemies within the dungeon. Multi-player turn-based derivatives such as

TomeNET,

MAngband, and

Crossfire do exist and are playable

online.

[26]